The Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg

The building: an ‘arena of scholarship’

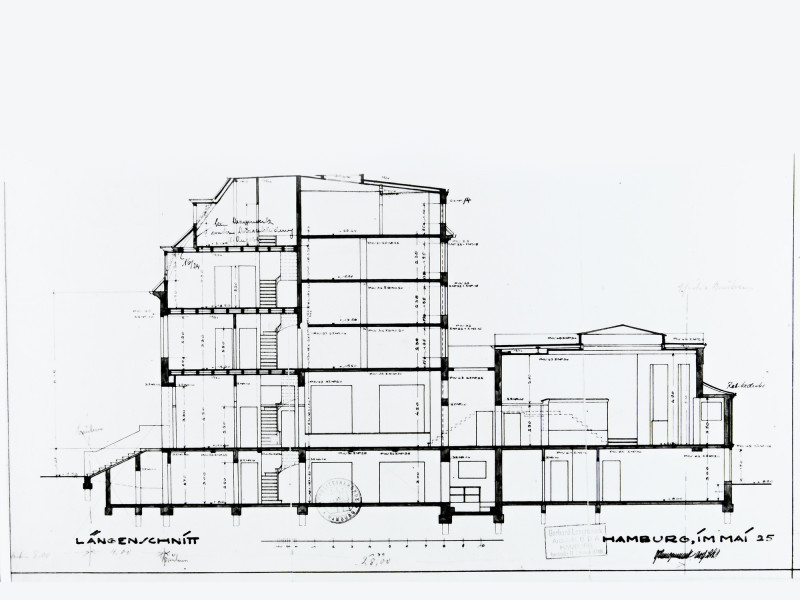

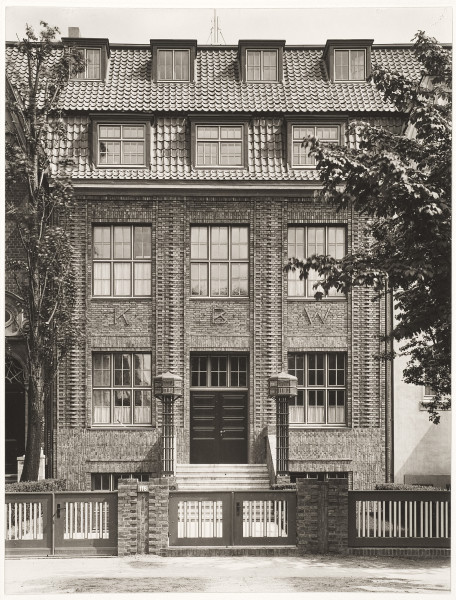

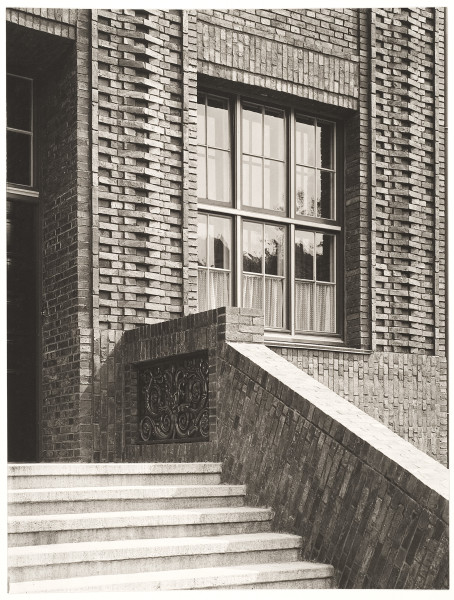

The Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg (K.B.W., Warburg Library of Cultural Studies) at no. 116 Heilwigstraße was built from 1925 to 1926. Designed to fit into a narrow plot directly beside the private residence of the Warburgs at house number 114, where the library along with improvised lecture rooms and office had previously been housed, the new building was to provide an adequate and representative space for the now well-established institution. The K.B.W. was opened on 1 May 1926 with a speech given by Ernst Cassirer, marking the completion of its development from a specialised book collection run by a student and private scholar to a (semi-)public library of cultural studies. The close ties between Warburg and his library were reflected in the layout of the new building complex, for instance, in the lift that connected all floors of the library with the house.

The architect of the K.B.W. was Gerhard Langmaack who had been recommended for the job by Fritz Schumacher, the chief building director of the City of Hamburg and a friend of Warburg. Schumacher had proposed various ideas for the design of the building, which was then developed by the architect and client, with much consultation and debate, and paid for by Warburg’s brothers.

1925 – 1926

PLANUNG UND BAU DES BIBLIOTHEKSGEBÄUDES

Historische Pläne und Fotografien zur Dokumentation des Baus in Eppendorf.

the ellipse

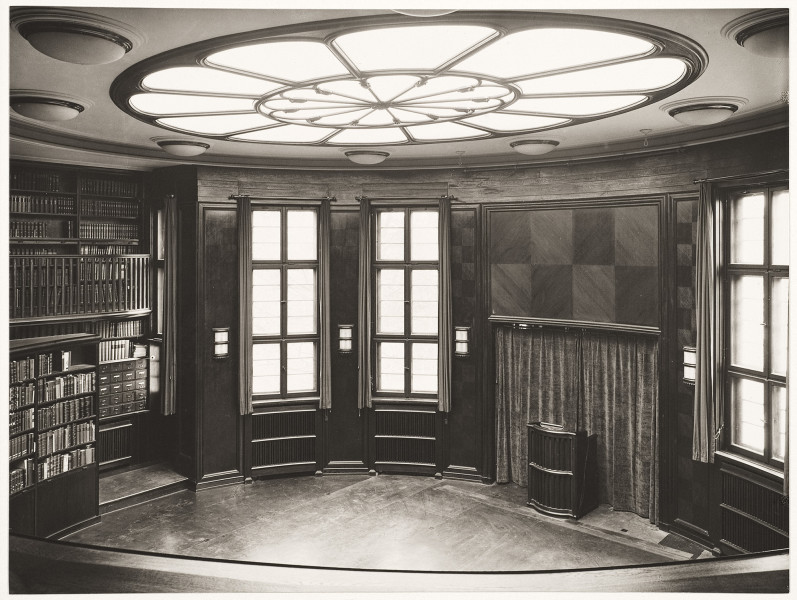

Behind the brick facade, which recalls Schumacher’s great public buildings, is a rationally structured building comprising offices spread over three storeys facing the street, a four-storey tower to house the collection of books and an ellipsoidal reading room and lecture hall that stretches into the garden. For Warburg, the ellipse as the defining element of this space was central to the design process.

Die Decken-Ellipse als Symbol

Als exemplarisch für die architektonische Sorgfalt und die Liebe zum Detail darf Aby Warburgs keineswegs rein ästhetische Entscheidung bei der Einrichtung seiner Kulturwissenschaftlichen Bibliothek 1926 gelten, der Decke des Lesesaales die Form der Ellipse zu geben. Das elliptische Oberlicht gibt diesem Raum sein auffälliges und gefälliges Format und ist dabei ein absichtsvoll platziertes Symbol. Die Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg war mit ihren 60 000 Bänden der Erforschung des Nachlebens der Antike gewidmet. Im Fokus steht damit die Renaissance. Den Denkern der Renaissance war die von Johannes Kepler 1605 entdeckte, 1609 veröffentlichte elliptische Form von Planetenumlaufbahnen ein Zeichen dafür, dass es Freiheit im Kosmos gäbe. Aby Warburg hat sich – durch den befreundeten Philosophen Ernst Cassirer darin ausdrücklich bestätigt – für die Ellipse entschieden, um diese kosmologische Freiheitsidee der Renaissance im Bewusstsein zu halten und das Programm der Freiheit wissenschaftlicher Forschung in symbolischer Form zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Die Ellipse mit ihren zwei Brennpunkten war für Warburg überdies Zeichen eines Weltverhältnisses, das zwischen zwei Polen schwankt: zwischen Mythos und Logik, Magie und Mathematik, konkretem Körper und abstraktem Zeichen, manischer Bewegung und melancholischer Hemmung,. Das Verhältnis der Gegensätze lässt sich nur bedingt als kontinuierlichen Fortschritt fassen – vielmehr widmet sich Warburg den historischen Vermittlungsleistungen. In diesem Sinn war die Ellipse für Warburg Energieform, in der die Spannung zwischen den Gegensätzen präsent gehalten ist.

Latest technology

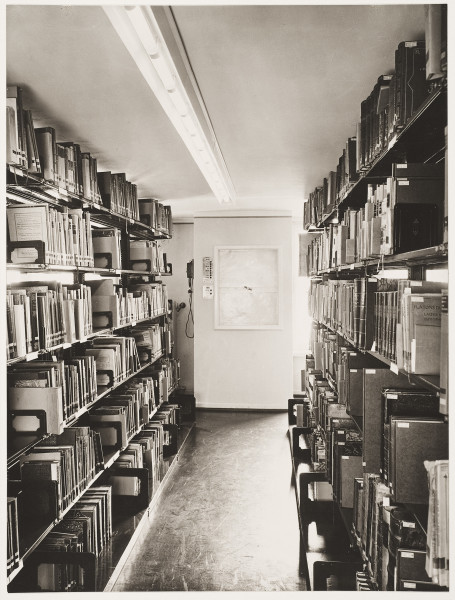

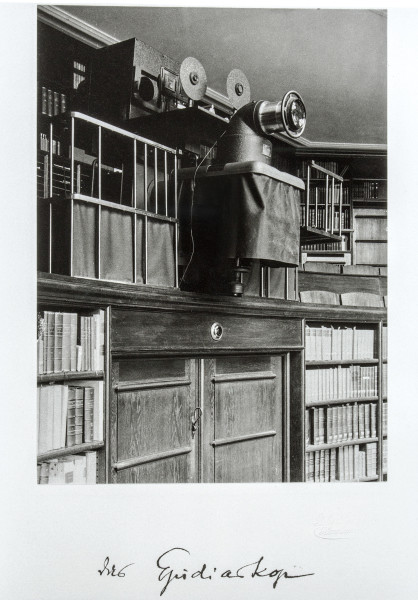

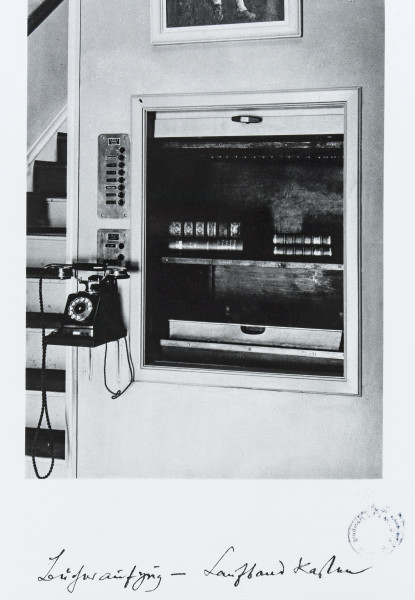

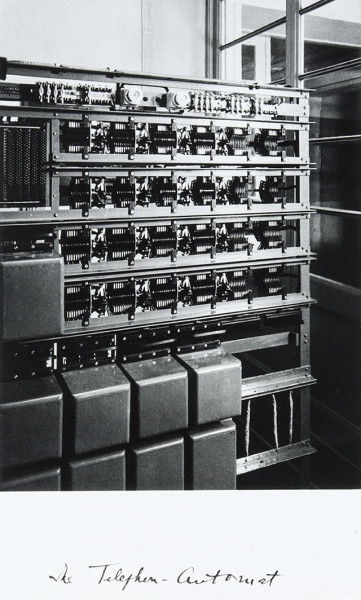

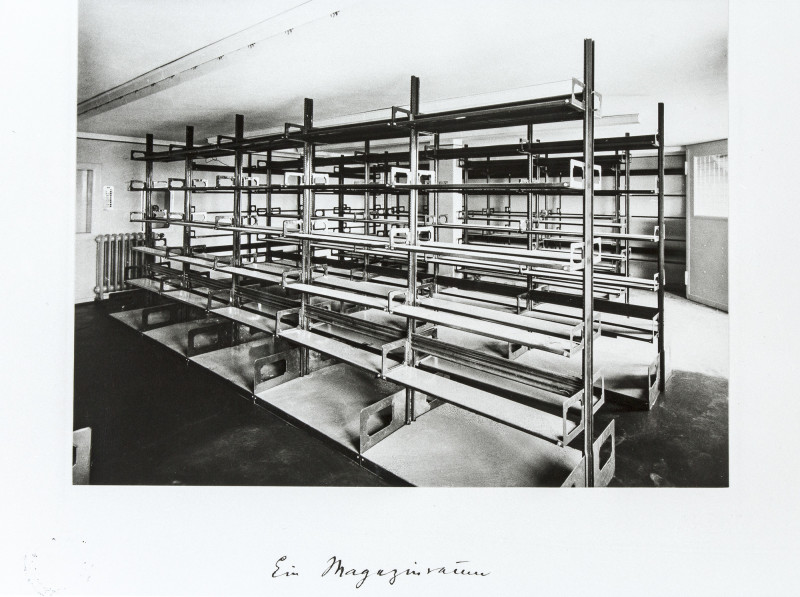

He also placed considerable importance on the integration of the functions of auditorium and study hall, which he described as an ‘arena of scholarship’ where he gathered visual and written material for his research. As there was only room for a small open-shelf collection in the reading room, books were mechanically transported from the closed stacks to a niche in the reading room, in a fast-moving technological feature that was considered astonishingly futuristic at the time. State-of-the-art equipment was also acquired for use during lectures and seminars.

High-tech at the K.B.W.

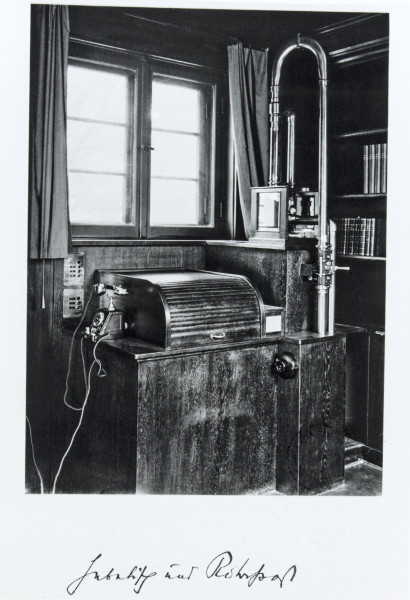

Aby Warburg not only equipped his institute with an extensive photo library but also with the most advanced technology of his day for reproducing and projecting images. The reading room had its own modern epidiascope that was capable of double projections and could even be used with self-made colour transparencies to compare images. Commenting on his lecture on Orientalisierende Astrologie (Orientalising Astrology) in a letter to Ludwig Binswanger from 6 October 1926, Warburg mentioned the great number of images that accompanied the lecture (‘spanning a period of about 4,000 years’) and went on to stress the significance of modern reproduction technology: ‘What proved to be a great help in this attempt was that our photographic machine—a “Photoclark” from Dr Jantsch in Überlingen—allows one to reproduce a great number of images in a very short space of time without glass negatives.’ The art historian was fully aware that his comparative working methods and emphasis on demonstration were dependent on the material resources of his image lab. He noted in the library’s logbook on 24 January 1928: ‘Without access to a photographer in-house, the development of the “new method” would not be possible.’ Although Warburg often used technical metaphors in his speech, he was sceptical of some of the modern inventions of his day and blamed contemporary forms of communication, such as the telegraph and telephone, for a ‘loss of distance’ that threatened our ‘space for contemplation’. Yet he certainly made use of these accomplishments for the day-to-day running of his research institute which was equipped like a modern bank or office. The K.B.W. was fitted with numerous telephones and a pneumatic post system to ease the communication of requests for loans within the library, as well as a conveyor belt installed under the floor and a special lift that quickly brought the books from the closed stacks to the reading room without disturbing readers.

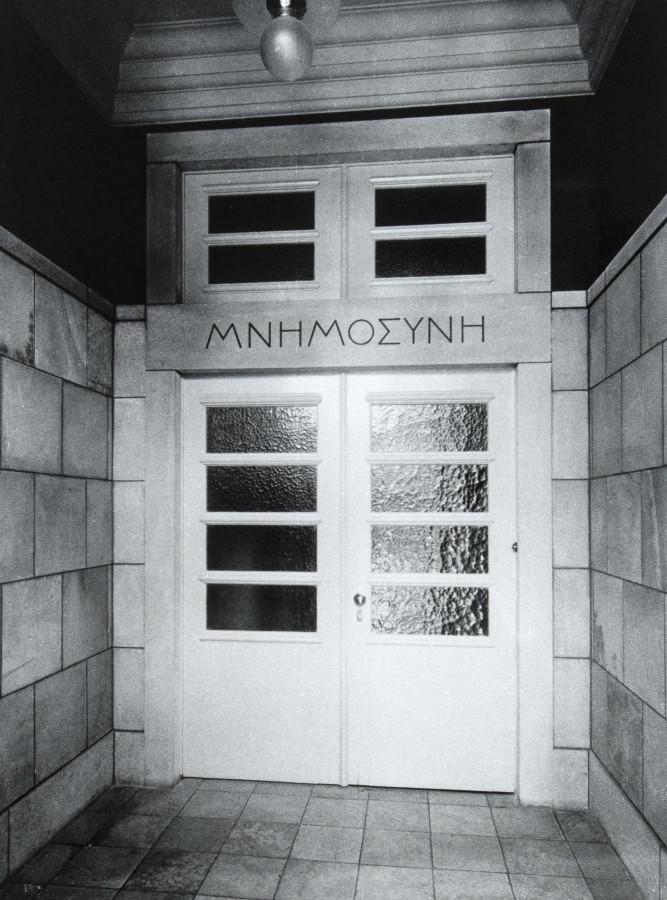

Mnemosyne – dedicated to memory

The word “mnemosyne” is inscribed in Greek letters above the entrance to the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek. Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory and the mother of the nine Muses, symbolises Aby Warburg’s approach to art history. His life’s work was devoted to his attempt to conceptualise antiquity’s influence on the modern age as a product of the processes of cultural memory. Impressions of classical images and ideals are stamped on our minds like a memory and recalled, as it were, in the art of the modern age.

Images, as the metaphor of memory suggests, possess a life of their own. They are not only part of a continual tradition and consciously appropriated, but at certain times reappear after long absences like revenants (Wiedergänger), reclaiming their validity.

Visual memory

The phenomenon of a Western collective visual memory had preoccupied Warburg since the 1890s. In his notes on Ausdruckskunde (the theory of expression) that accompanied his thesis on Botticelli, Warburg theorised that the artistic recourse to formulaic images from antiquity was a performance of memory. Artists dealing with intense events, crises and radical change subconsciously reproduced visual formulas for extreme emotional states. From theoreticians such as Ewald Hering and Richard Semon, whose research in perceptual psychology and evolutionary biology proposed that memory traces are inherited, Warburg borrowed the terms ‘engram’ and ‘mneme’, with which he described the encoding and storage of images in the psychic apparatus and the artistic organism. Warburg particularly focused on the semantic shifts that visual formulas experience in their new contexts. Rather than focusing—in terms of conventional iconography—on the petrified meaning of pictorial motifs, Warburg sought to trace their historical development—within the context of his own understanding of iconology.

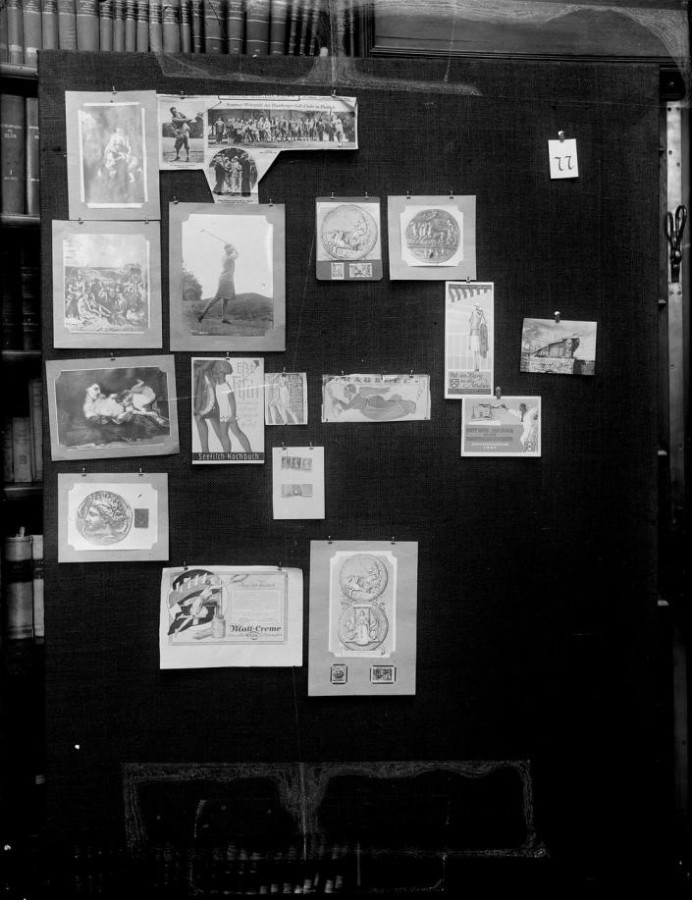

Picture sequences – the ancient world lives on

The individual dynamic of this ‘afterlife’ becomes visible in the Mnemosyne Atlas, which Warburg began in the mid-1920s. It comprises a series of arrangements of photographs, mostly affixed to wooden panels covered with black fabric, depicting sculptures, reliefs, frescoes, paintings, artistic and scientific drawings and sketches, as well as playing cards, pictures from newspapers and advertising graphics. Laid out in intersecting rows and arranged in different sequences, they trace the transformation and interpretation of particular visual formulas from antiquity through to the 20th century: for example, the figure of a dancing maenad from an ancient relief who reappears as a maidservant mid-stride in Ghirlandaio and again in the image of golf champion Erika Sellschopp, arm raised after playing a shot. The pose and silhouette remain the same, but the semantic content is definitively altered. His montages were initially conceived as a research tool, but he soon began to use them as a pedagogical instrument, displaying them at lectures, and later in accompanying exhibitions.

Series and exhibitions of images

After he was released from the Kreuzling sanatorium of Ludwig Binswanger in 1924, Aby Warburg only published a small number of writings. Nonetheless, the last years of the art historian’s life were extremely productive. Warburg conducted research, went on study trips and drafted numerous important lectures. Significant works from this time include the Mnemosyne Atlas, which remained unfinished at the time of his death, as well as a dozen series of pictures and exhibitions that were meant to accompany lectures. The type and length of his lectures attest to the experimental nature of Warburg’s work in the laboratory of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek. A particular example of how he used his later lectures and accompanying exhibitions as a true testing ground is his introduction of the visual montage as a didactic medium that offered multiple possibilities for identifying interrelationships and replaced the clear linearity of oral reconstructions with visual simultaneity. Warburg developed the format of the ‘picture atlas’ into an independent medium in which he recreated the polyphone and polyfocal argumentation structures of his sequences of images. As open configurations of knowledge, they possess both epistemic and aesthetic dimensions, their layouts seeking both intellectual and sensual cognition. Warburg was convinced that the subject matter of his research—the ‘afterlife’ of classical artworks that capture an existential state of excitation, their incorporation into social (visual) memory, the permanent oscillation between superstition and enlightenment—could be made clearer by presenting the works rather than just describing them in words. By juxtaposing and aligning the selected reproductions, he aimed to replace the rather mechanical model of interrelated influences proposed by art history with a more comprehensive theory of the ‘migration of images’ derived in cultural psychology. Aby Warburg’s picture series and exhibitions were reconstructed for the first time in 2012 in an annotated publication.

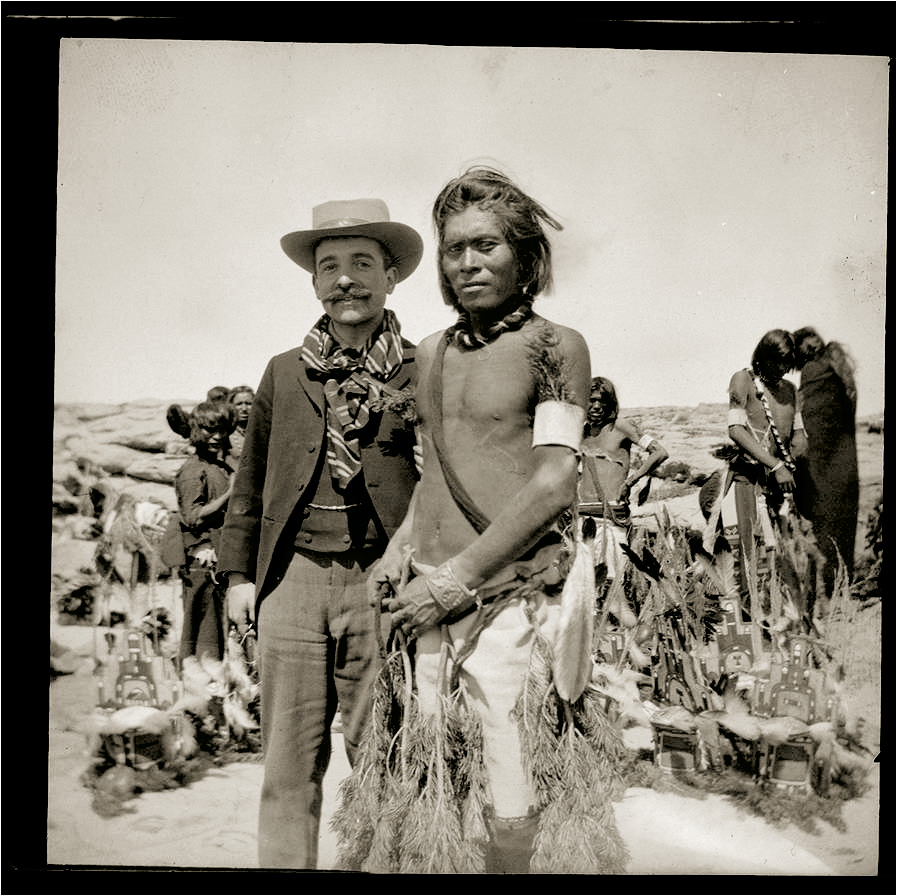

Crossing borders – the history of art as a cultural science

Warburg’s research led him far beyond the field of art history. From the painters of the early Florentine Renaissance to their patrons and their iconolatry, Warburg went on to study comparative mythology, the cults of the ancient world and the rituals of Central American natives at the close of the 19th century. He explored the relationship between magical thought and modern technology, nature religions and the natural sciences within Western European traditions, covering late medieval astrology, early modern mathematics and modern technology. Warburg formulated his theories with reference to a wide variety of disciplines, such as evolutionary biology, physiology, psychology, ethnology, theology, philology and linguistics. The Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek was both the result and the fundament of Warburg’s cross-disciplinary research at the fringe of conventional art history, in which the complex of references and quotes in his writings was given an accessible order.

Series of books – acquisition and arrangement

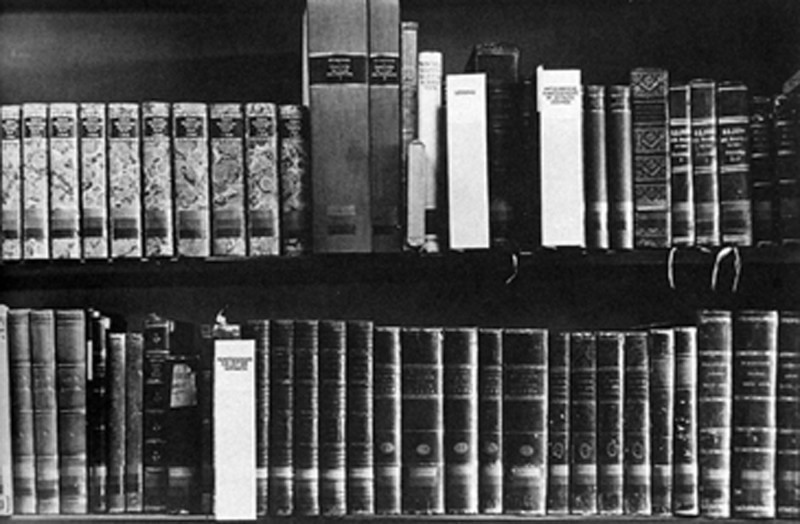

It was around 1900 that Warburg first discussed with his brothers his plan to expand his private library and transform it into a public research institute. Over the next thirty years, the library’s holdings grew steadily: from 15,000 in 1911 to 20,000 in 1920. The new building for the K.B.W. on Heilwigstraße was designed to house 120,000 volumes. The classification and arrangement of the books followed an unusual system developed by Warburg. In line with the principle of the ‘law of the good neighbour’ (“Gesetz der guten Nachbarschaft”), he placed works on the history of the natural sciences beside books on magic, divination, astrology or alchemy in order to illustrate the crossover from magic and cults to modern science. The order of the books charts Warburg’s own individual way of thinking and researching that has proven beneficial until today.

The ‘law of the good neighbour’

The K.B.W. was structured in four departments under the headings ‘Orientation’, ‘Image, ‘Word’, and ‘Action’, which spread across the four floors of stack rooms. The order of the departments changed many times, but their layout remained more or less the same. Under the heading ‘Orientation’, Warburg grouped works that deal with humanity’s position in the cosmos (superstition, religion, magic, science), including works from the fields of anthropology, theology and philosophy as well as the history of the sciences. In the sections ‘Word’ and ‘Image’, writings on art theory and the history of the arts documented the artistic expression of historical changes around the world, while ‘Action’ encompassed works from history, law, ethnology and sociology, as well as studies of theatre and festivals. Each book was assigned to three sub-categories recorded in its threefold call number, based on subject, text type and historical-cultural field. The books were not ordered alphabetically on the shelves, however, but according to the ‘law of the good neighbour’. The idea behind this concept was to enable readers to discover books that they were not actually looking for, but possibly needed even more than what they had originally sought. This surprising arrangement, combining books from different subject areas, aimed to build bridges between the disciplines and spark new questions, perspectives and insights.

The K.B.W. – a place of research

The K.B.W. was always more than a library. The reading room was designed from the outset to function as an auditorium too, with the appropriate acoustics and space for regular lectures and talks, as well as seminars organised by the art history department at the Universität Hamburg. A lively exchange evolved between the scholars who came to be known as the ‘Warburg circle’. The group included students from the newly founded University of Hamburg and the academic staff of the K.B.W., such as Fritz Saxl and Gertrud Bing, as well as the well-known scholars Erwin Panofsky and Gustav Pauli (art history), Karl Reinhardt (classical philology), Richard Salomon (Byzantine history), Hellmut Ritter (Oriental languages) and Ernst Cassirer, who taught at the Universität Hamburg. The lasting fascination that Aby Warburg’s foundation of the K.B.W. set in motion is documented not least in the publication of the interdisciplinary periodicals Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg (Lectures of Warburg Library) and Studien der Bibliothek Warburg (Studies of Warburg Library). Both periodicals were brought back to life when the house was reopened in the 1990s.

Exkurs Warburg and Cassirer

coming soon

Emigration

1933

After Aby Warburg’s death on 26 October 1929, the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek was still reeling from the impact of the global economic crisis. However, the first existential threat to the future of the research institute was the rise of the Nazi party in Germany. By 1933, relocating to Italy, which Warburg had contemplated during his lifetime, was no longer possible because of the political situation. Other countries were also considered but finally, thanks to co-worker Edgar Wind’s contacts in England, an agreement was reached to move the library and its staff there, initially for a period of three years.

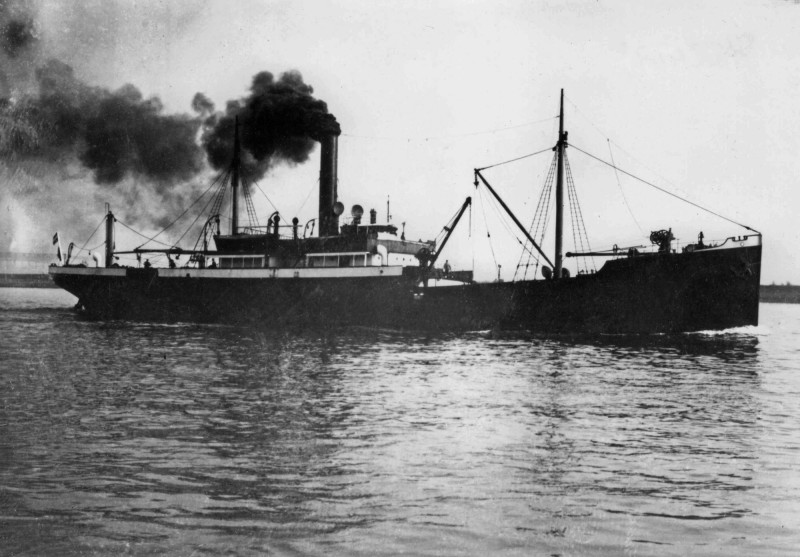

On 12 December 1933, the cargo ship Hermia set sail for London, where Fritz Saxl, a longstanding colleague of Warburg and director of the library after his death, had negotiated the fate of the research institute with the support of Lord Lee of Fareham and Sir Samuel Courtauld. The books together with the extensive collection of photographs escaped on board the Hernia to their new home in exile, followed some weeks later by all of the shelving and equipment, marking the arrival of the K.B.W. with its rich intellectual history in the academic circles of the British capital. An intense exchange between German and British research traditions ensued and in 1944 the institute was incorporated into the University of London.

This singular act of a forced ‘overseas loan’ turned into a permanent, but ultimately successful situation as the K.B.W., under its new name of the Warburg Institute, was able to grow in London to become one of the best-known research institutes for the humanities in the world. In 2013, the Warburg-Haus in Hamburg and London’s Warburg Institute held a joint conference accompanied by a publication to commemorate the emigration of the K.B.W. and its influence on research and scholarship in Britain

The house in Hamburg served as the head office of various companies until the 1990s, including the Neue Deutsche Wochenschau GmbH, which produced the first German current affairs programme Tagesschau, as well as a pharmaceutical and an advertising company. In 1983, it was listed as a landmark-protected building. After fifty years in commercial hands, the building was purchased by the City of Hamburg in 1993 and renovated. The oval reading room, Warburg’s ‘arena of scholarship’, was restored to its former state in line with conservation standards. Since then, the ‘Warburg-Haus’ has once again been dedicated to promoting scholarship.

Picture Credits

© The Warburg Institute Archive, London; Warburg-Archiv im Warburg-Haus, Hamburg